1992

Land mines emerged as one of the key factors affecting the poor in Cambodia. Once again I discovered that the things which make people poor are often external and imposed. On this occasion, the Nine Network current affairs program, Sunday, decided to do a feature story on the land mines problem in Cambodia. My colleague Steve Levitt and I were there to help them get their story.

Around this time, World Vision became serious about campaigning for a complete abolition of land mines. This visit firmed up my own resolve about the rightness of this crusade.

Bring Them Back, And Dump Them

The situation in Cambodia was changing every day. A measure of serious attention was being given to the appalling problem of mines. Nevertheless, the UNHCR plan was still to bring some 370,000 people back from the border camps within a few months.

Our work in Battambang province, the main area to which the returnees would come, revealed that this was a very dangerous proposition. At best, the returnees would be confined for a long time to holding camps designed for one week's stay. At worst, they would return to land still dangerously mined. The result would be death and injury.

Few organisations were giving attention to the development needs of the people after they arrived. The recent resignation of the local UNHCR representative had something to do with this concern. Plans for demobilising the various militias were also inadequate. I feared this would lead to former soldiers turning to banditry. There was already evidence of this.

Communications inside Cambodia were difficult. Outside Phnom Penh, impossible. Some aid agencies had installed their own communications facilities. I was very impressed with the development work I saw being supported by World Vision. The level of local ownership of the process was very high and I felt we were truly 'fighting poverty by empowering people to transform their world'. This phrase had become our mission statement at World Vision Australia.

Get Up Early

After a restless night in Bangkok I got up at 3.00 a.m. to shower and check out. David Chandler, World Vision's regional adviser for Indo-China, had asked me to be at the airport at 4.00 a.m. for the 6.00 a.m. flight. Mark Janz, from the Relief Department of World Vision's international office, was also going in on our flight. David's advice was based on the slow processing of Thai Immigration. on the way in it took an average of five minutes to process each person (I timed them!). If you were last in a line of a dozen people, you could expect to stand there for an hour.

As it turned out we picked the one morning when the airport was deserted. This gave me a chance to have a long conversation with John Holloway, the Australian Ambassador to Cambodia, who was also on our flight. John knew me and World Vision well. He had been Ambassador in the Philippines when Ruth Henderson was field director there before her marriage to Harold Henderson (chief executive of World Vision Australia 1976-1988). He was the sort of ambassador who disliked the party round of diplomacy. 'Too much vapid talk with people who have more money than morals,' he said.

The flight was a little late but otherwise uneventful. There was a brand new terminal at Phnom Penh built for Sihanouk's return the year before. Judy Moore, one of a number of Australians working for World Vision in Cambodia, had wormed her way around the officials to be waiting for us at the edge of the tarmac. A Khmer woman slid us by the immigration and customs officials.

Don't Drink The Water

As we drove into town, Judy pointed out some boys filling a tank of about 200 litres with murky water from a hyacinth-infested pond.

'They take it into town and sell it to restaurants.' Advice: don't drink the water. Bottled water is available, although a colleague advised me to be suspicious if the bottle had been opened before it came to the table. I had brought bottled water from Thailand anyway.

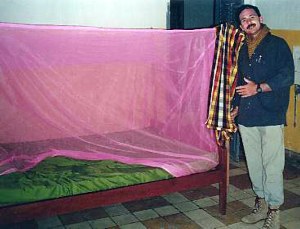

Hotels In Town

We checked into the Monorom Hotel. My room was as good as any I had used in Vietnam, with one working light, a hot water heater in the shower and an air-conditioner in the wall.

Although the air-conditioner worked, the weather was too cold to use it. I had left my jumpers in Thailand thinking they would be excess baggage, but in the evenings it was almost cold enough to have pulled one on. Even the locals were concerned at the 'cold snap'. Mind you, I doubt it dropped below 20 degrees C.

Another surprise was the Cambodiana Hotel where we went for dinner on the first night. It was a fully-fledged five star international class hotel with bars, marble floors, spic and span staff, good food and a swimming pool. I was glad not to be staying there frankly: while its room rate of about A$150 a night was not very expensive in world terms, the hotel was a bit over the top in this place.

In contrast, the room rate at the Monorom was only about A$40 a night. David and Mark told me that the rats in the roof top restaurant at the Monorom were 'as big as cats'. I decided right away that I wasn't eating there.

What Do You Think Of Our Town

What Do You Think Of Our Town

A few people asked me what my impressions of Phnom Penh were. The kind of question I always find hard to answer. I said I thought it would be quieter and smaller. I imagined a country town feel, whereas it felt more like Da Nang or Hue in Vietnam. It was busy and noisy, with a constant thrum of vehicles and the emasculated squeaks of countless motor cycle horns. There didn't seem to be any known road rules, and since many of the drivers and riders had only become mobile in the previous year we had a nation of L-platers (although L-plates were non-existent too).

Human Mine Clearing

On arrival I had discovered that Steve Levitt, a freelance communications expert working with World Vision, was up country in Battambang investigating the possibility of taking the Sunday film crew there. In this area there was a mine in the ground for every man, woman and child in Cambodia, and plenty more left over for the 370,000 people who were on the border and planning to return that year, beginning in April. When they arrived, unless these mines were found and removed we could have a human mine clearing operation. Already in this country it was easier to get blown up by stepping on a mine than to catch chicken pox in Australia.

A start had been made on mine clearing but recent experience in Afghanistan was not encouraging. Most mines had been laid without proper records. People going about their ordinary daily life in the rice paddies, grazing cows, collecting firewood, were being maimed every day.

In Australia, I reflected, manufacturers had some measure of responsibility for the proper use of their products. If General Motors built a car that had the unfortunate habit of blowing up in the neighbour's driveway, they would be made to recall it. What we had in Cambodia was a defective product. It was creating an environmental disaster much worse than if someone sailed an oil tanker up the Mekong and spilled its contents over the countryside. And it was not cormorants and baby seals that were being killed, but seven-year-old kids looking after the cows and pregnant women bending down to pull up rice stalks.

What responsibility had the countries and companies who supplied these cowardly and obscene devices? They should invest properly in their effective recall. The USA, UK, China, the former USSR, Vietnam and the ASEAN countries all supplied these disgusting rmnes. They did so, they said, because they had the future of Cambodia at heart. If they wanted to avoid being labelled hypocrites, they needed to fund the mine clearing operation to an effective level.

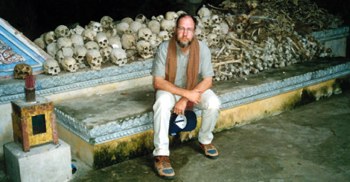

Killing Fields

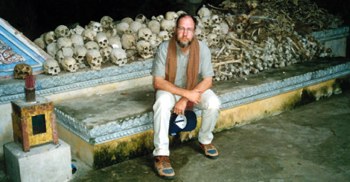

Understanding Cambodia must begin with some appreciation of the 'killing fields', so while I waited for Steve to return, Clinton Moore, the teenage son of Peter and Judy, took me to the Toul Sleng Genocide Memorial.

Toul Sleng was a school which Pol Pot turned into a torture centre. Thousands went through ritual torture here before being sent to their death. Once inside there was no reprieve. Photos covered wall after wall, taken by the officials before and after torture. Whole families were interred together to ensure no-one was left to complain.

It reminded me of the similar 'school' in Kampala where Idi Amin had imprisoned the victims of his paranoia. One telling difference here was the methodical manner of the processing. More like the Nazis. I had seen much of the darker side of humanity in these past few years.

The school was right in the middle of the city, but fifteen kilometres south of Phnom Penh was a killing field. Here they had exhumed nearly 9,000 bodies and piled their skulls into a gruesome pagoda. It gave a grisly sense of awful suffering.

Champagne For My Birthday

The early start had left me quite tired, so I went back to my hotel and had a snooze. Steve arrived during the afternoon and we agreed that the real story for Sunday was up in Battambang. This would mean a flight up country and an overnight stay.

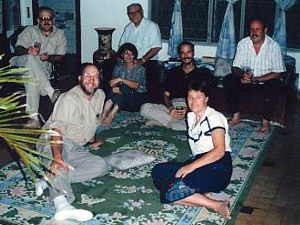

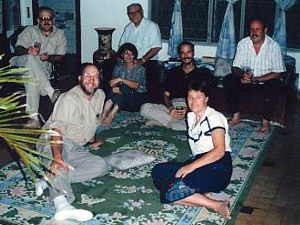

In the evening we went to the Cambodiana for dinner with Jayasainker, the local World Vision operations manager, and Justin Byworth, the relief manager. After that we went around to the Moores' again and Frank Webster (the finance manager, but temporarily in charge) arrived with a bottle of champagne to celebrate my birthday. Judy Moore had baked a cake too. Frank was quick to point out that World Vision had not spent money on buying champagne. A supplier had given us this bottle as a gift and he'd been waiting for an appropriate excuse to use it.

In the evening we went to the Cambodiana for dinner with Jayasainker, the local World Vision operations manager, and Justin Byworth, the relief manager. After that we went around to the Moores' again and Frank Webster (the finance manager, but temporarily in charge) arrived with a bottle of champagne to celebrate my birthday. Judy Moore had baked a cake too. Frank was quick to point out that World Vision had not spent money on buying champagne. A supplier had given us this bottle as a gift and he'd been waiting for an appropriate excuse to use it.

We met Paul Lockyer and his Sunday crew and agreed to fly up to Battambang the next day. This called for Steve and Judy to do some scouting. Phones didn't work in town, so arranging a plane trip meant endless cyclo rides trying to find people.

Planes Without Address

There was only one small plane for hire in Cambodia and that was a single-engined Cessna. It was run by an organisation called Aviation Sans Frontieres There must be some relationship with Medicins Sans Frontieres (the French group 'Doctors Without Borders'). This group had recently moved office, so Steve nick-named them Aviation Sans Address.

In the late afternoon, I made a short visit to the National Paediatric Hospital. I was glad to see this institution that has been so much part of World Vision's history in the country. As in any hospital, many patients are in heart-breaking situations, but I was comforted to see that the facility was of a good standard, especially for Cambodia. It contrasted dramatically with the appalling hospital we would visit the next day.

Postcards From Home

Gilles Guillard, a French-born Aussie who was our hospital administrator, met me and said, 'So! This is the Philip Hunt who keeps sending me postcards from strange places.' It was my habit to send postcards to Australians working overseas during my travels. Of course, I hadn't met all of them.

Once in Romania, a colleague happened to sit next to a pleasant young man on the flight into Bucharest. His name was Philip. Imagine her romantic surprise when a postcard from Philip turned up a few days later, wishing her well. Over the next few months, she received some more postcards from Philip. These only added to her confusion.

'He's not very romantic', she commented one day to a colleague.

'That's because he's your boss.'

Guided By Satellite

Guided By Satellite

The flight to Battambang next day took one and a quarter hours and this plane had the first GPS navigation system I had seen. They soon became common-place, but at the time they were rather amazing. The pilot, Claude, was an ageing Frenchman wanting to do something for Cambodia. Aviation Sans Frontieres just served the aid agencies and did not accept commercial charters. Steve had described Claude as 'having a face like a map of the Swiss Alps', so I easily recognised him when he entered the coffee shop at the airport.

At Battambang air strip a white Toyota Land Cruiser arrived with a very large blue World Vision flag flying from the back. Inside were Paul and Helen Davies from Britain, who were then living in Battambang preparing our new program there. They were a young couple in their twenties who met in the border camps in Thailand when Paul was working for Christian Outreach and Helen was nursing there.

Another Bad Hospital

Our first stop was the Military Hospital. Most of the seventy-two patients were amputees caused by land mines. The place was appalling: run down, dirty and almost totally without resources. The operating theatre, where they carved off legs and arms, had the wind blowing through it and a floor stained with blood.

'What are you lacking?' I asked Paul.

'Everything. Antibiotics, antiseptics, anaesthetics, bandages.' I stopped him before he got to the C's.

Every Hotel Is A Date

Our hotel was called The October 23. I'm not sure why. A driver said it was 'a French day'. It was a four-storey building in the middle of town wedged between apartment blocks of similar height. My room on the third storey was mouldy and stained, though reasonably clean. Outside at the end of the corridor were two squat toilets. As the irreducible minimum for me is a clean, operating flush toilet (I'm just too Western for less) this hotel didn't pass muster. It turned out to be amazingly noisy too, with voices echoing around all night.

Our hotel was called The October 23. I'm not sure why. A driver said it was 'a French day'. It was a four-storey building in the middle of town wedged between apartment blocks of similar height. My room on the third storey was mouldy and stained, though reasonably clean. Outside at the end of the corridor were two squat toilets. As the irreducible minimum for me is a clean, operating flush toilet (I'm just too Western for less) this hotel didn't pass muster. It turned out to be amazingly noisy too, with voices echoing around all night.

Next day we checked into the January 7 hotel. At least we knew that January 7 was the day Cambodia was liberated from Pol Pot.

This seemed like a palace by comparison, although the differences only amounted to en suites (with working toilets and cold showers) and a mirror on the wall.

Dangers For Children

The riverside café provided breakfast, omelettes, but I stuck to café au lait, et du pain avec Vegemite. We headed off for Rattanak Mondol, a district towards the Khmer Rouge-held hills where returnees were supposed to go. We stopped at a camp for Internally Displaced People (you are not a 'refugee' until you cross a border).

Paul Lockyer did a 'walk' and an interview with me for his report.

One thing frightened me at this camp: the number of uncovered wells. They were an open invitation for a child to drown in. The wells were about a metre wide and five metres deep, and if anyone fell in, it would be very difficult to get them out. I mentioned this to Paul and, although World Vision didn't have administrative responsibility there, he hoped to take it up with whoever did.

Dangers In The Forest

From there we went to an area down the road where people were trying to re-establish themselves on their original farms, having fled the Khmer Rouge the previous year. The place was littered with shrapnel, bits of shells, mines, rockets and so on. If I had gathered all that I saw there it would have filled the front foyer of our home back in Australia.

I spoke to one woman. 'Uncle goes out into the nearby mine-infested woods to cut firewood', she said. 'He stacks it and sells it to people who come looking for firewood. He'd like to take it to the market, but we have no transport. We have gradually sold everything to buy food.'

'Isn't it dangerous in the forest?'

'Yes, but he treats it like an adventure. Anyway', she said, 'he has no other occupation. There is nothing else he can do.'

Nowhere Safe

Resettlement in this area was a very high risk proposition. The governor had surveyed the area and estimated there was enough safe and farmable land for 500 families. He was expecting 34,000!

Paul's report made it clear that there was now no plan to put the returnees back on their farms. Although the official scheme was for them to go to transit camps for a week, they would have to stay much longer. There was simply not enough good land available. UNHCR's job was to bring them back. Who picked them up then?

The biggest amount of money and effort would be required after they returned. Our plan, titled the Returnee Re-integration Program, involved providing a mobile health team, agricultural development for all three groups (locals, internally displaced and returnees), renovating some medical facilities (such as the military hospital) and re-training (providing new skills for demobilised soldiers, the disabled and novice farmers). Some of these activities would be directed to internally displaced people, some to local communities. Some would be quick impact projects of less than $20,000, such as the building of a school. Our rehabilitation efforts would be concentrated in Phnom Penh because that was where most of the amputees were.

Another Killing Field

Another Killing Field

We had lunch in a dubious little restaurant in a little village market, then visited a mountain, on top of which was the remains of a temple turned by the Khmer Rouge into a killing place. A pipe had been stuck through one wall so that blood caused by head injuries could be more easily drained away.

A few metres away down a pleasant path were two spectacular limestone caves full of bats, spiders and sinewy tree roots. In the first a bench had been built, and skulls, bones and bits of clothing were piled up on it carefully. The remains of people killed by the Khmer Rouge. In the second, a small pyramid had been made with the same repellent material. Draped over it was a decaying corpse, its clothing still attached.

While the TV crew filmed it from every angle I went back to the temple where the view was spectacular and the air fresher. 'Except for what happened here', said Helen Davies, one of our Battambang project managers, 'this would be a lovely place to come.'

next chapter - "The reporter was a Prime Minister"

What Do You Think Of Our Town

What Do You Think Of Our Town In the evening we went to the Cambodiana for dinner with Jayasainker, the local World Vision operations manager, and Justin Byworth, the relief manager. After that we went around to the Moores' again and Frank Webster (the finance manager, but temporarily in charge) arrived with a bottle of champagne to celebrate my birthday. Judy Moore had baked a cake too. Frank was quick to point out that World Vision had not spent money on buying champagne. A supplier had given us this bottle as a gift and he'd been waiting for an appropriate excuse to use it.

In the evening we went to the Cambodiana for dinner with Jayasainker, the local World Vision operations manager, and Justin Byworth, the relief manager. After that we went around to the Moores' again and Frank Webster (the finance manager, but temporarily in charge) arrived with a bottle of champagne to celebrate my birthday. Judy Moore had baked a cake too. Frank was quick to point out that World Vision had not spent money on buying champagne. A supplier had given us this bottle as a gift and he'd been waiting for an appropriate excuse to use it. Guided By Satellite

Guided By Satellite Our hotel was called The October 23. I'm not sure why. A driver said it was 'a French day'. It was a four-storey building in the middle of town wedged between apartment blocks of similar height. My room on the third storey was mouldy and stained, though reasonably clean. Outside at the end of the corridor were two squat toilets. As the irreducible minimum for me is a clean, operating flush toilet (I'm just too Western for less) this hotel didn't pass muster. It turned out to be amazingly noisy too, with voices echoing around all night.

Our hotel was called The October 23. I'm not sure why. A driver said it was 'a French day'. It was a four-storey building in the middle of town wedged between apartment blocks of similar height. My room on the third storey was mouldy and stained, though reasonably clean. Outside at the end of the corridor were two squat toilets. As the irreducible minimum for me is a clean, operating flush toilet (I'm just too Western for less) this hotel didn't pass muster. It turned out to be amazingly noisy too, with voices echoing around all night. Another Killing Field

Another Killing Field