People in our business often talk about the difference between relief and development. Such talk is nonsense. It shows lazy thinking. The tendency to compartmentalise and divide the real world into boxes of black and white is undisciplined thinking. It may look disciplined, because it is neat. But so is juggling with one ball. It’s neat because it is simplistic. And stupid.

Too often, undisciplined thinking leads to rules and regulations that put straitjackets around people. The people of the old Communist world know this only too well. But rules and regulations do not equal discipline: they equal control. One doesn’t need discipline to remain in handcuffs.

Discipline is only needed when we have freedom. Remaining still when one’s hands are free requires discipline. Juggling three balls requires discipline.

It is the same with thinking. When we divide things into boxes, we are lazy and undisciplined thinkers. When we operate in the real world of open and complementary categories, we need disciplined minds to keep all those balls in the air.

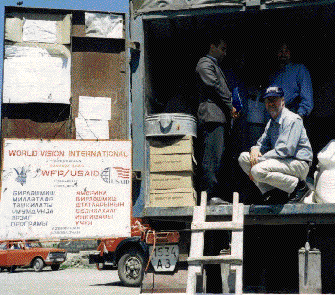

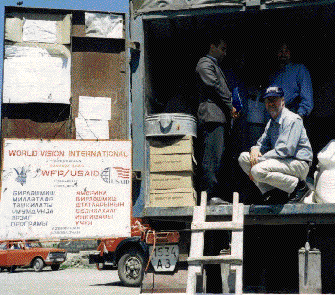

That’s why this work that World Vision was doing in Azerbaijan should not be categorised as “relief” or “rehabilitation” or “development.” It was some of all of these things. We were rehabilitating buildings, bring people relief from the suffering of improper shelter, and doing it all in a way that developed community and sustainable change.

Steve, from Liverpool, UK, contained more enthusiasm than his Englishness could release easily. After visiting a wrecked building he said, “An engineer’s delight! There’s so much we can do!”

He also cautioned me against standing too close to one of the electricity substations.

“You might get arc-ed” he said as I stood near the evil ganglia of thick wires exuding through the door and windows of the small brick building. I stepped back.

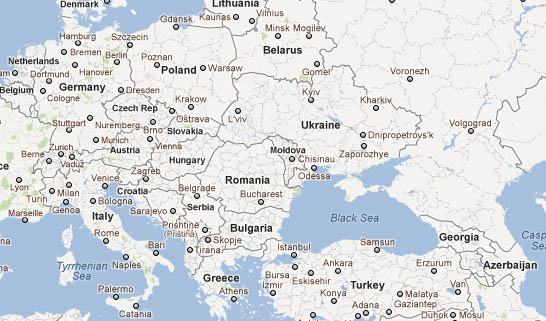

Some history. As the Soviet system crumbled after 1988, Azerbaijan and its neighbour, Armenia, fought a territorial war. History, which didn’t care much about nationhood or national borders until recently, had permitted an enclave of Armenians to live in an area surrounded by Azeris. To cut a long and bloody story short, Armenia won. Armenia occupied all of the area known as Nagorny-Karabakh and the bit of Azerbaijan in between. 853,000 people were displaced and now live in other parts of the country unable to return home. Many of them lived in Sumgayit—a long way from home.

Back at the office the cook provided lunch, an Azeri dish of chicken and herb rice. To my surprise, the staff welcomed me with a gift, a small carpet in the colours of the Azerbaijan flag, and the pattern of the Azerbaijan map.

Next we drove through the city to our meeting with the deputy Prime Minister, Mr Rustamov, a former philosophy professor now responsible, among other things, for humanitarian affairs and reportedly very helpful to the aid agencies. I thanked him for this support sincerely and enjoyed a briefing on the situation of the country that he gave with well-rehearsed and practised ease.

At five, we were due for an office-warming party to which many in the NGO community had been invited. Since it was not yet four, Stu asked if I would like to walk in the old city. Of course, I did. We walked by an ancient stone wall, adorned with marksmen’s slots and small towers. New and old buildings pressed around it along narrow lanes. The architecture, an interesting mixture of East and West. A doorway here resembling the front of an Austrian apartment block. Around it a stone building that would not look out of place in Jerusalem. In architecture, and in many other respects, Azerbaijan is a place between cultures.

After some easy meanderings we came by the Maiden’s Tower which apparently was once by the shore of the Caspian Sea. Now the sea is a few hundred metres away and below. But I was told it was on the rise again.

“Why is it called the Maiden’s Tower?” I asked looking up at this massive tower shaped in an unbalanced ellipse and a full seven storeys tall.

“I don’t think anyone really knows,” Stu replied. “Some say her father built it to keep her protected from unwelcome suitors. Others that she built it to protect herself from an abusive father.”

Around the base of the tower carpet sellers show the products for which Azerbaijan continues to have a good reputation, although I heard it was moderately complicated to get them out of the country.

Downtown was a large fountain square although the fountain wasn’t running. Here one saw the modern side of Baku with well-dressed people hurrying about business and shopping. We stopped for a coffee and enjoyed the company of the rich, young people of Baku. Obviously some people had money in this town. All the latest fashions of Europe were on show. Blue jeans and jackets. Leather. Red hair. Girls with platform shoes that made their miniskirts appear teasingly shorter. Boys with designer-tattered trousers and Men In Black sunglasses.

Back at the World Vision office things had begun to hop. Vanessa-Mae was playing on a CD-player and all the staff were smiling a welcome and offering soft drinks and nibbles. The NGO community were all present and clearly knew one another well. Sometimes people think we are in competition with one another. This is rarely true. Cooperation and support are the more common experience. Unfortunately, there is always more than enough work to go around without us getting in each other’s way!

After a few hours of meeting new people my attempt to remember names was turning my brain into mush. When I began to forget my own name even though I was drinking Coke, I decided to sit quietly in a corner for a while.

Around eight, Stu took me off to his apartment where my morning companion, Steve, was to be joined by Scott and Carrie, young married American colleagues for dinner. Carrie had agreed to prepare a meal and had gone hunting for chickens. Contrary to the plan, Carrie had the keys to Stu’s flat and had not arrived before we did. I filled in time wandering through the street vegetable market outside Stu’s apartment block. Garlic, tomatoes, onions of various kinds, cucumbers and other things were in plentiful supply. A few years ago, under Communism, such markets were unheard of.

Stu had been lucky to find a lovely apartment, especially since he’d had no time to look for himself. Dinner was delicious. Barbecue chicken, vegetables and potatoes. Carrie had an open, honest face that suggested a short distance between heart and sleeve. Her husband, Scott, had chiselled All-American boy looks and a ready smile. Around the dinner table we talked about our experiences in this World Vision business. And since Stu and I had been in it about twenty years longer than the others, mostly they were our stories.

Wednesday, 13 May 1998

Around eight we left for the road south. Our destination was Imishili in the south-west of the country. On the drive out of Baku, I started to get an idea of Carolyn’s ironic description of depressive beauty. The outskirts of town were littered (it’s the right word) with abandoned oil pumps. Thousands of rusty skeletons in a jumble of dead iron and oil sludge. A Mad Max landscape. In one place, an immense oil rig was dismembered in sections on its side. It towered four times above the height of three-storey buildings. All abandoned and useless.

There is oil in Azerbaijan, but interest has moved to the Caspian Sea itself. Working oil rigs could be seen offshore. In one place, a new oil rig was being built in a dry dock.

Once out of town our driver, Roman, picked up speed to 100 kays. As it turned out the roads in Azerbaijan are generally of good quality. At 60 kays. Many are four lanes wide, or wider, and, at least outside of the towns, free from potholes. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the quality of the foundations because, at speed in a four-wheel drive, it’s a bit like riding Space Mountain at Disneyland. Bumpy is too polite a word for it. After two days of these roads, I said ironically to Stu, “I think we should go and find some really bumpy roads now. I don’t think I have been shaken up quite enough yet!”

Roman proved to be a good driver when not too tired. His anticipation seemed good and I commented to Stu that I thought there was a relationship between driving and strategic thinking.

“You can tell a good strategic thinker by the way they drive,” I said. “Good drivers look ahead and anticipate possible events. Many drivers don’t do this. They just have to have good reactions, and be good at avoidance. It’s the same in business. Good leaders look ahead and anticipate possible events. When problems occur they have long ago taken corrective action. For good strategic thinkers and drivers, it all looks like plain sailing.”

Once we left Baku, we were immediately in the desert. The Caspian Sea was light blue and calm to our left, and to the right was sand and low hills. After about an hour, we turned west and crossed a river near Gazi-Mammad and immediately the landscape turned green. Although relatively dry, only the strip of land by the Caspian is a true desert. The rest appears fertile and productive.

Scattered here and there along the coast were small communities of limestone block houses, sometimes their existence and location merely at the whim of some distant central planner. Such communities had been built around factories which were now defunct. What life was left for people in this terrain?

The traffic comprised mostly Ladas, those Fiat 124 copies that are still produced more than thirty years after the original 124 event. Somewhere along the way we stopped for morning tea, very salty goats’ cheese and flat bread. It was nourishing and we enjoyed a pleasant break from the bouncing Galloper in the open-air shade of a small teahouse.

By lunch time we arrived in Imishili, not far from the border with Iran. World Vision had taken over a World Food Program food distribution project from another agency a few months before. Running the team was an Ethiopian, Debebe, who gave me the best briefing on food distribution that I had heard in all my World Vision time! Recently awarded a PhD from the University in Baku, Debebe, had a mind like accounting software. Arrayed along one wall were all the forms used to check, crosscheck and double crosscheck that the food distribution was going without hitch or loss. He guided me through this maze with stunning logic and bewildering clarity. I say “bewildering” because, frankly, I have always found these complicated accountability systems totally bemusing. I was bewildered to find that I wasn’t bewildered!

No-one in World Vision underestimates the importance of accountability in food distribution. It is perhaps the Achilles’ Heel of the aid business. It is so easy to lose or waste food through sloppy procedures. Over the years, World Vision has built a virtually foolproof system that ensures accuracy and security. The system has been completely documented in our internal systems and faithful application of the procedures ensures outstanding performance. In Imishili, a loss rate of 0.004% and an excess rate of 0.04% caused probably by slight shortages when measuring flour and other commodities out of the sacks. As impressively small as these numbers were, it was even more impressive that they had been measured with such accuracy.

And, consistent with our disciplined thinking about our business, food distributions were being done in a developmentally sound way. Local people are engaged to take responsibility for much of the organisation and to even participate in the control and checking procedures in addition to full-time monitors attached to every distribution.

After this tour de force I was ready for lunch which we enjoyed with Debebe’s staff in their office. We had yoghurt and greens, delicious sugared strawberries, and bread, rice and chicken followed by a question and answer time. The first question was revealing. It came from one who had been employed by the previous agency and who had lost his job suddenly when the agency stopped working without much warning. He wanted to know if World Vision was committed to stay. I assured him that we were, but reminded him that our ability to stay rested on quality work that impressed donors enough to continue to support us. So he played a hand in World Vision’s long-term prospects too.

One young woman asked if people in Europe knew about Azerbaijan? I replied that I did not think so. That, even in Europe, people do not know history well. Many think Azerbaijan (which has thousands of years of history astride the Silk Road) only came into being in 1991!

We looked at the warehouses containing the flour, oil, and other things for distribution. Debebe said the previous agency had received these warehouses free, but the owner then insisted that all his relatives be employed. Perhaps this led to corruption. Our policy is to avoid such cosiness, not that we have anything against families working together, but we know from experience that even the most honest person can come under enormous pressure from family obligations. Best avoided.

On the drive north, with the no-go mountains of Nagorny-Karabakh rising to snow-tipped heights to our left, we bounced by Ladas stuffed to the roof lining with various vegetables.

“Oh, look,” I said with surprise on spotting the first one, “a cabbage car!” The Lada had hundreds of cabbages in the back seat, pressed against the windows up to the roof line. Roman showed no real surprise and I was soon to discover that what was new to me, was commonplace here. Soon we passed another cabbage car, then a tomato car, and finally a few onion cars. Imagine a car full of onions on a warm day!

As we moved further north, we saw more houses with elaborate tin rooves, and every now and then had to slow for herds of sheep and cattle grazing by the roads.

Our destination was Ganja, the second biggest town in Azerbaijan and once the capital. In Soviet times it had been a military town, closed to visitors. From there, the first crack troops invaded Afghanistan. We were to see, the next day, how their barracks were being used in a new way today.

The World Vision office in Ganja was the base for a microenterprise loans scheme and a nutrition research unit. The microenterprise loans scheme was managed by a local man, Mustagil, and an American, Tammie, managed the nutrition research. Tammie occupied one room in the local guest house and we dropped our bags there before joining some of the local staff for dinner in the open air high on a hill overlooking the town.

For the first time since arrival I was offered alcohol. Azerbaijan is a Muslim country but it was clear from the many bottles and cans of Vodka available alongside Coke and Fanta at roadside stalls that there was little strictness about alcohol use. The alcohol offered in this case was Vodka. This proved to have a uniquely medicinal aroma and flavour. Trying to balance cross-cultural clumsiness with humour, I quietly labelled it “E.R brand” after the American TV show of the same name, suggesting it would go well on swabs. Drinking only enough to follow the toasting around the table, and swamping it with ample supplies of Coke, we enjoyed a meal of cooked meat and greens.

Back at the World Vision guest house I found my bedroom was downstairs through a door made for the vertically challenged. The room was of adequate height and comfortable, but it seemed no-one had worked out how to get into this part of the house until it was already built. Stu slept on top of the garage, which had been converted into a kind of patio. This  seemed sensible since the night air was merely cool, but the mosquitoes arrived to annoy him. After we shared a digestive and some conversation, we retired and I drifted off to the muted sounds of a dog’s yapping and a distant conversation.

seemed sensible since the night air was merely cool, but the mosquitoes arrived to annoy him. After we shared a digestive and some conversation, we retired and I drifted off to the muted sounds of a dog’s yapping and a distant conversation.

Thursday, 14 May 1998

The toilet wouldn’t flush, but we found a bucket. The water in the shower was hot, but the drain water ran out from under the bath, across the tiled floor and down a drain hole in the middle of the room. I wasn’t complaining. Yesterday, after looking in the warehouse, we had wandered across some railway tracks and seen where some hundreds of refugees were now living.

I say “refugees” although the official title is “internally displaced people”, usually abbreviated to IDPs. Personally, I think this kind of categorical language is just another form of abuse. Technically, you cannot be a refugee until you cross a border. But since most borders are, to say the least, contentious, what right does one authority or another have to categorise people like this? These IDPs can look across a new border, an unofficial border caused by an unresolved conflict, that separates them from their homes. They are seeking refuge, no matter what label we put on them.

These refugees in Imishili were living in old railway carriages. In winter they are cruelly cold: in summer, stinking hot. Many had built a ramshackle lean-to against their part of the railway carriage to try to make life more bearable. Many of these people had been there for more than five years.

So the odd plumbing of the World Vision guest house in Ganja would have been a blessing to them. And I counted my blessings as I prepared for another day.

“Why did you join the Peace Corps?” I asked Tammie while sipping coffee. She had come to World Vision after a stint in Sri Lanka in the Peace Corps, and working in public health in Senegal.

“It was something I always wanted to do,” she replied. “My parents encouraged me. I think they wished they had done something like this when they were younger.”

Mustagil and his colleagues took me on a tour of some of the loan clients. First we visited a busy factory in the middle of a former military barracks that was pressing sugar into cubes. A thriving concern, the owner had borrowed money to buy machines and had quickly repaid the loans.

In one of the dormitory style buildings, once occupied by the Russian Blue Berets, and still adorned with official Russian military graffiti extolling the pride of the air force, we visited a family that had developed a dressmaking and tailoring business.

We dodged around the “hub cap holes” on the way out of town. Manholes were everywhere, and some of them actually had covers. Most did not, so it was important to avoid dropping a wheel into one of them. For sure, it would rip off your wheel, stub axle and all.

On the hills near the town was a new community of stone and mud houses, delineated by wandering stone walls and accompanied by chickens, sheep and goats. This was the new farming and business community of refugees who had transferred their lifestyle to near-town, rather than in-town. It seemed to me a thoroughly more satisfactory arrangement with a better quality of life more like the farming lives they had abandoned a few years before.

Here, World Vision was helping a family of brothers who had a bootmaking business. They had bought lasts with loans and had little trouble selling their shoes in the markets.

As we left, one of the loan officers said to me, “They like to work. If you like to work, you have a future.”

For lunch we drove to nearby Mingechevir a small and attractive town with wide tree-lined streets beside the huge Mingechevir reservoir. Myles, a young Englishman who had acted with distinction as country director for a few months during the hiatus in leadership before Stu arrived, was now firmly in place running the combined food distribution and microenterprise development project.

Food was actually being distributed this day at Mingechevir so we were treated to this side of the program in operation. It was running like a well-oiled machine. Many of the Azeris working for World Vision spoke good English which I appreciated since I had only learned yesterday my first word of Azeri—how to say “Thank You”. Tomorrow I would try for “Good-bye.”

Food was actually being distributed this day at Mingechevir so we were treated to this side of the program in operation. It was running like a well-oiled machine. Many of the Azeris working for World Vision spoke good English which I appreciated since I had only learned yesterday my first word of Azeri—how to say “Thank You”. Tomorrow I would try for “Good-bye.”

It turned out that many of these people were former teachers. After meeting the tenth or eleventh school teacher I asked, “If you are all working here, who is teaching in the schools?”

“There are too many teachers for the jobs available,” came back the reply, which I discovered was diplomatically only half the truth. The full story had to do with what a local school teacher gets paid. Less than USD 30 a month. Whereas a controller at a food distribution gets USD 100 a month. Pure economics at work. Hopefully, the government will do something about teachers’ salaries soon.

Again we enjoyed lunch with the staff, this time with the pleasant addition of rich onion soup. The office in Mingechevir was in a building that looked like it had really been an office, whereas all of the other places I had been in were converted houses or flats. This one also had theatre seats bolted to the floor! Part of the office was a small theatre that would have held an audience of about 30 people. A small stage had been walled off and converted into the record keeping room for the food distribution documents.

We had time to visit one of the clients of the microenterprise project. It was a family living in the former boat sheds by the river. In their living room were three incubators full of eggs. Outside was a small chicken run where part of the last batch showed that those incubators were working OK. Around the corner of the house sheep skins were being tanned into leather for jackets.

We had time to visit one of the clients of the microenterprise project. It was a family living in the former boat sheds by the river. In their living room were three incubators full of eggs. Outside was a small chicken run where part of the last batch showed that those incubators were working OK. Around the corner of the house sheep skins were being tanned into leather for jackets.

The project manager, Durdana  , a small woman who looked like she could command authority in inverse proportion to her height showed us this with evident pride and not a little dismay that we could not also see the other eight clients she had on her list.

, a small woman who looked like she could command authority in inverse proportion to her height showed us this with evident pride and not a little dismay that we could not also see the other eight clients she had on her list.

By three we needed to leave for the three hours back to Baku and my flight out. The drive took us up into the mountains and spectacular views across the plain and then across rolling hills. Unfortunately, the roads were as bumpy as ever.

At one spot a series of boys was selling something in small plastic packets. When I asked what it was, we stopped and bought a packet of mint-flavoured tea leaves.

“Good medicine,” Roman explained. Stu offered to let me have them, but I said I didn’t want to explain them to narcotics sensitive customs officials in London or Vienna.

About an hour out of Baku, the terrain suddenly switched back to desert sands and by seven we were at the airport again. There was only one flight out that night, mine to London. It was scheduled for 9.15 P.M. and already a half dozen people had arrived but the entry to the check-in counters remained closed. I dispatched Stu and Roman with thanks and waited.

Soon I saw a queue begin to form so I joined it in about fifth place. Beside us was a door labelled “Business Class” and soon people arrived there and went in. Those of us in economy class, or what British Airways dresses up as “World Traveller Class”, were made to wait until the business class line was empty before permitting us to continue to the single x-ray machine.

In addition, a gaggle of flash looking people arrived with metal cases individually labelled “Case 1”, “Case 2” and so on. Right up to 30. These cases were deposited at the front of the line and Azeri fixers soon appeared to try to persuade the military doorman to give their clients priority. It was clear I was going to be standing in this queue for a little while.

After about 40 minutes, the four world travellers in front of me had been admitted to the inner sanctum. I stood an inch from the young soldier’s face while he looked around my left ear at something extremely important in the middle distance.

The younger American behind me expressed his impatience as another dribble of Business Class passengers arrived and gazumped our place on the x-ray machine.

“Who are these people?” he asked the younger soldier who just looked at him like he had spoken a foreign language. Funny.

The American added something in Russian that seemed to register on the soldier, who merely shrugged. It was obviously out of his control. I didn’t hold a grudge.

“The way I think about it is this,” I said gently to my queue companion. “We all have to get on the same plane. We can either wait out here, or wait in there. The only advantage in there is that you can sit. But you have to pay a lot more for Business Class for the privilege of a seat inside.”

This seemed to mollify him but this was the moment when the Azeri fixers for the many-cased party found their cousins on the other side, and admission was created for them. This delayed us another fifteen minutes and caused the younger American behind me to explode with a four-letter word.

A man in a suit was helping to pass the metal cases through. Overhearing this supportive word from my companion, he turned to me as he heaved another heavy case and said, “I’ll bet you’ll never complain about overweight again after seeing this.”

I smiled. “I’ve travelled with a film crew once or twice myself,” I assured him. “I don’t mind.” Then I added, “Who are you with?”

“CBS Sixty Minutes,” he replied, “if that means anything to you.”

I assured him it did.

Gradually the cases went through and about five of the CBS team were admitted through the Business Class door while another fifteen or twenty waited in our line.

“You see that man with the grey hair next to the guy you spoke to?” asked my American companion.

“Yup.”

“He’s the CBS News Correspondent for this region.” He said his name but it didn’t mean anything to me. “He’s a big time news man. Maybe I’ll ask for his autograph. At least I’ll get something out of this waiting.”

I considered this. It would be no thrill to me to get the autograph of “a big time news man.” I clearly did not value fame like my companion.

“I tell you what,” I said. “I’ll give you my autograph. Then you can tell people you got it from a complete nobody who endured an hour in a queue with you in Baku. No-one else can claim that little piece of fame except us!” He looked at me like I was a bit looney, which of course was probably accurate.

“Forgive me for saying so,” I persevered foolishly, “but I’m cynical about the big time news media.” He looked interested so I kept going. “Look at this guy. He is surrounded and protected by at least twenty people here. He gets special treatment in airports. What do you think happens when he goes into a village? Does he even go to villages? How can he have any idea what is going on in the real world? He doesn’t touch the real world.”

Of course, there was part of my own dilemma expressed in this. I had seen people living in railroad cars, but I didn’t have to live in them. I had seen people receiving food supplements, but I didn’t have to live on them. I had wandered the dark corridors of dilapidated buildings, but now I was standing in a queue for an aeroplane that would fly me to London and on which they would ply me with food and drinks.

Did I have any idea what was going on in the real world? In World Vision’s business one needs to soberly assess what one has seen and experienced and let it enter your heart till it hurts enough to be real.

“Do you have any carpets?” the customs official asked me when I finally got my bag from the x-ray machine from the hands of a man who had offered to help me for ten dollars. I couldn’t stop him from helping me, but I knew I could bargain about the price later.

“Yes, I have one.” The official’s eyes brightened and I wondered if I was in trouble. “But it’s a small one.”

“It’s in your case?” he asked. A-hah, an unbeliever. “May I see it?”

I opened my case and showed him the one foot square carpet the staff had given me as a souvenir. He looked disappointed.

“Isn’t it nice?” I asked. “Map and flag together. Nice souvenir.”

“Show me your currency declarations.” He was moving on. I produced the forms.

“You have a problem,” he said.

“No,” I said carefully. “I don’t think I have a problem.”

“Yes,” he explained, “you need to get this one stamped when you come into the country.”

“I didn’t know that,” I said with honest amazement. Like, how could one know what to get stamped? “I showed it when I came in and he didn’t stamp it. I’m sorry about that.”

“Next time you should get it stamped, then there will be no trouble.” Trouble? I doubted there was going to be trouble. He must see hundreds of unstamped currency declarations if my experience was a guide.

“Thank you very much for your advice,” I replied with hardly evident sarcasm. “I’ll certainly know what to do next time.” He waved me on so he could look for bigger carpets.

“Ten dollars,” my porter said. I gave him one.

“No, ten,” he said presuming I was deaf. He had not helped to speed me through customs one bit, and the American who had been behind me in the line was now ahead of me in the check-in queue.

“No,” I said gently. “One dollar is good. Thank you very much.”

“Five,” he tried.

“No,” I laughed. “Thanks.”

“You have Azeri money?” He was a trier this one.

“No. Thank you and God bless you.” Now that was uncalled for, I thought, dismissing a pesky porter with a blessing. But he left, with a tip as big as a school teacher’s daily wage.

Be still, be still, my soul; it is but for a season:

Let us endure an hour and see injustice done.

—A.E. Housman (taken out of context)

next chapter - more journeys dracula's castle 1999

You can get to Baku, Azerbaijan, from anywhere in Europe. For our region of Middle East & Eastern Europe, Baku represents the eastern boundary. Three time zones from Central Europe and as many hours flying—if you can get a direct flight—which you usually can’t from Vienna.

You can get to Baku, Azerbaijan, from anywhere in Europe. For our region of Middle East & Eastern Europe, Baku represents the eastern boundary. Three time zones from Central Europe and as many hours flying—if you can get a direct flight—which you usually can’t from Vienna. seemed sensible since the night air was merely cool, but the mosquitoes arrived to annoy him. After we shared a digestive and some conversation, we retired and I drifted off to the muted sounds of a dog’s yapping and a distant conversation.

seemed sensible since the night air was merely cool, but the mosquitoes arrived to annoy him. After we shared a digestive and some conversation, we retired and I drifted off to the muted sounds of a dog’s yapping and a distant conversation. Food was actually being distributed this day at Mingechevir so we were treated to this side of the program in operation. It was running like a well-oiled machine. Many of the Azeris working for World Vision spoke good English which I appreciated since I had only learned yesterday my first word of Azeri—how to say “Thank You”. Tomorrow I would try for “Good-bye.”

Food was actually being distributed this day at Mingechevir so we were treated to this side of the program in operation. It was running like a well-oiled machine. Many of the Azeris working for World Vision spoke good English which I appreciated since I had only learned yesterday my first word of Azeri—how to say “Thank You”. Tomorrow I would try for “Good-bye.” We had time to visit one of the clients of the microenterprise project. It was a family living in the former boat sheds by the river. In their living room were three incubators full of eggs. Outside was a small chicken run where part of the last batch showed that those incubators were working OK. Around the corner of the house sheep skins were being tanned into leather for jackets.

We had time to visit one of the clients of the microenterprise project. It was a family living in the former boat sheds by the river. In their living room were three incubators full of eggs. Outside was a small chicken run where part of the last batch showed that those incubators were working OK. Around the corner of the house sheep skins were being tanned into leather for jackets.